The Price Cap Trap

![]() The Price Cap Trap

The Price Cap Trap

President Trump has a knack for putting his finger on real pain points — and then setting off alarms across the financial system. His latest idea does both.

President Trump has a knack for putting his finger on real pain points — and then setting off alarms across the financial system. His latest idea does both.

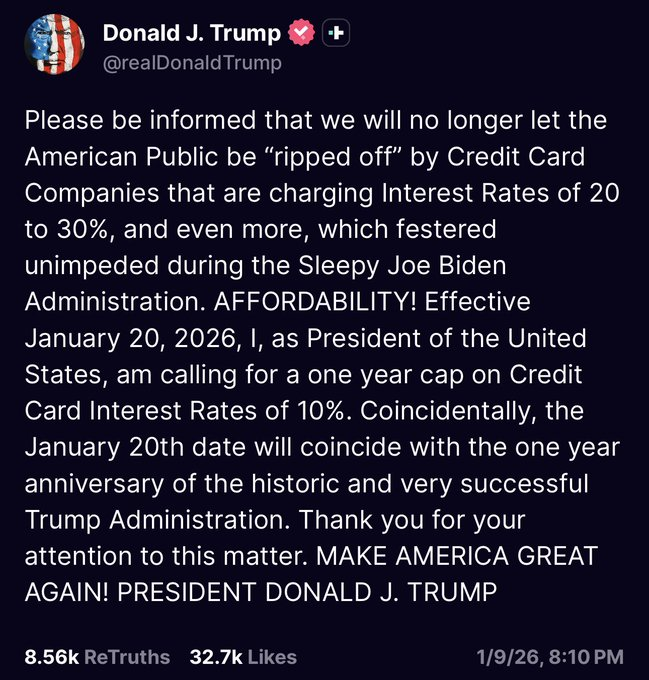

More than a week ago, Trump called for a one-year cap on credit-card interest rates at 10%, starting today, Jan. 20.

(As of now, the 10% cap remains a proposal and political initiative — not a binding policy or law.)

The idea seems straightforward: With Americans squeezed by high borrowing costs, Washington should step in and force relief. With many credit cards charging interest rates well above 20%, the proposal hits a cost-of-living nerve.

For its part, the banking industry responded immediately — and forcefully.

Financial institutions warn that a hard cap would not simply lower rates. It would dramatically shrink access to credit.

Financial institutions warn that a hard cap would not simply lower rates. It would dramatically shrink access to credit.

The Electronic Payments Coalition (EPC), which represents banks and payment networks, says that under a 10% cap, credit cards would become economically unviable for most borrowers outside the top tier.

According to the group's analysis, accounts tied to credit scores below 740 — around 82–88% of all open credit-card accounts — would likely be closed or severely restricted.

“A one-size-fits-all government price cap may sound appealing,” EPC Executive Chairman Richard Hunt says, “but it wouldn't help Americans — it would do the exact opposite, harming families, limiting opportunity and weakening our economy.”

That claim sounds self-serving, but the mechanics behind it are real.

Credit cards are unsecured loans. There's no collateral backing them.

Credit cards are unsecured loans. There's no collateral backing them.

The interest rate compensates lenders for default risk, fraud and the reality that many cardholders revolve balances for long periods while making only minimum payments.

Credit card APRs hit 25.2% in 2024 — the highest since 2015, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. And more cardholders are making only minimum payments, a sign that households are stretched thin and lenders are getting nervous.

Trump's argument is that a rate cap would reverse that dynamic — lowering costs for consumers, boosting spending and improving affordability.

But Paradigm's macro expert Jim Rickards says history offers a blunt warning.

“In 1980, during the last year of Jimmy Carter's presidency, inflation and interest rates seemed out of control,” Jim explains.

“In 1980, during the last year of Jimmy Carter's presidency, inflation and interest rates seemed out of control,” Jim explains.

“Inflation had been building since the late 1960s, but in 1980 it reached 13.5%… Interest rates reached an almost record high of 20%.

“On March 14, 1980, seven months before the election, Carter announced the authorization of credit controls,” Jim says.

The theory was simple: restrict borrowing, cool demand, bring inflation down. The result was the opposite.

“The policy was a complete economic failure,” Jim notes. “New credit card issuance stopped, and credit lines were capped.”

The economic fallout was swift. GDP plunged 8.5% in three months. Unemployment spiked from 6.2% to 7.8% by May.

By mid-1980, the controls were lifted. But the damage was done. A recession was already underway, and Carter went on to lose the November election in a landslide.

“Donald Trump is now using a similar tactic to fight the 'affordability crisis' and to tame inflation,” Jim continues.

“Donald Trump is now using a similar tactic to fight the 'affordability crisis' and to tame inflation,” Jim continues.

“That's not how credit works. The banks will simply cut off creditors, reduce credit lines and stop issuing new cards to consumers with lower credit ratings.”

That outcome is exactly what lenders are signaling today.

A study from Vanderbilt University's Policy Accelerator, meanwhile, estimates that a 10% cap could save Americans roughly $100 billion annually in interest costs.

“The profit margins are absolutely massive,” argues Vanderbilt's Brian Shearer, director of competition and regulatory policy. “There really is some fat to cut.”

Credit card rates are predatory. And price controls backfire. Both things can be true at once.

Credit card rates are predatory. And price controls backfire. Both things can be true at once.

The question isn't whether Americans are getting squeezed; they are. It's whether Trump's solution makes things worse.

The affordability crisis is real. The risk is that a policy designed to ease it ends up tightening credit, slowing spending and recreating the very economic stress it aims to relieve — just as it did more than four decades ago.

Jim concludes: “If Trump's idea goes through, put on your crash helmet because the economy will head down fast.”

The question now is whether Washington is about to make the same mistake twice, and whether voters will remember who was at the wheel when the economy stalls.

[Today marks one year since Trump’s inauguration.

If you were keeping a personal scorecard — wins and losses, promises kept and broken — are you better off today than you were a year ago?

Financially, professionally or in terms of opportunity: What’s changed for you? Hit reply and tell us where you stand. We’ll publish feedback throughout the week.]

![]() The Big MAC Trade

The Big MAC Trade

The market already has a name for what’s unfolding in Washington. As our pro trader Enrique Abeyta explains, economist Claudia Sahm has dubbed it the “Big MAC Trade” — a recognition that midterms are coming.

The market already has a name for what’s unfolding in Washington. As our pro trader Enrique Abeyta explains, economist Claudia Sahm has dubbed it the “Big MAC Trade” — a recognition that midterms are coming.

“With each new week, we seem to get another policy announcement aimed at affordability to win over voters,” Enrique adds. The goal is straightforward: “The Trump administration has one objective for the year, and that’s winning the midterm elections.”

Seen through that lens: “A one-year cap on credit-card interest rates makes little sense as serious economic reform,” Enrique argues. “If such a cap were truly beneficial and sustainable, it wouldn’t be temporary.

“The one-year duration lines up neatly with the election calendar, not with economic logic.”

But markets didn’t wait to parse those nuances. “Stocks of global payment and credit giants like Visa sold off sharply as investors rushed to price in worst-case scenarios.” In hours, a proposal with no legislative footing translated into billions in erased market value.

This is when experience matters.

“Markets don’t wait for legislation to pass. They trade expectations, probabilities and fear,” Enrique reminds readers. Election-year politics, in particular, tend to amplify that behavior.

“Markets don’t wait for legislation to pass. They trade expectations, probabilities and fear,” Enrique reminds readers. Election-year politics, in particular, tend to amplify that behavior.

For investors, the Big MAC Trade isn’t about dismissing risk — it’s about properly sizing it. “Understanding the political motivation behind it helps investors assess whether a sell-off reflects real long-term risk or temporary uncertainty.”

As midterms approach, Enrique expects affordability headlines — and volatility — to keep coming. That creates opportunity for those willing to look past the headlines and focus on fundamentals.

“Election-year politics may be noisy,” Enrique concludes. “But noise creates movement, and movement creates opportunity.”

And just like that, stocks are in free fall today. According to financial media outlets, Trump’s Greenland and fresh tariff threats are culprits for the sell-off.

And just like that, stocks are in free fall today. According to financial media outlets, Trump’s Greenland and fresh tariff threats are culprits for the sell-off.

Regardless, the tech-heavy Nasdaq is down 1.60% to 23,133 and the S&P 500 and Dow are down 90 and 590 points to 6,840 and 48,765 respectively.

Predictably, commodities are climbing. Oil’s up 2% to $60.62 for a barrel of WTI. And precious metals are shining: Gold’s up 3.50% to $4,758.50 per ounce; silver, meanwhile, is up 6.30% to $94.10.

Crypto, however, is not the safety play today. Bitcoin’s down 3.30%, just around $90K. And Ethereum’s lost a punishing 7%, just under $3K.

![]() Fed Foibles Push China Away?

Fed Foibles Push China Away?

China continues to pull back from U.S. government debt — and the move reflects more than routine portfolio adjustments.

China continues to pull back from U.S. government debt — and the move reflects more than routine portfolio adjustments.

According to U.S. Treasury Department data released this week, China reduced its holdings of U.S. Treasuries to $682.6 billion in November, down from $688.7 billion in October. That marks the lowest level since September 2008, at the height of the global financial crisis.

Measured against January 2025, China’s U.S. Treasury holdings are now nearly 10% lower, according to calculations by financial data provider Wind.

The decline is the latest step in a long, uneven retreat that began during Donald Trump’s first term. In March, notably, China slipped to third place among foreign holders of U.S. Treasuries, behind Japan and the U.K.

Shao Yu, chief economist at Fudan University, argues that China increasingly views the structure of U.S. borrowing itself as unsustainable. “The massive accumulation of [U.S.] debt resembles a Ponzi scheme, where larger volumes of new debt are used to replace the old,” Shao says.

“China doesn’t want to play this game anymore.”

China’s skepticism has been reinforced by growing uncertainty around U.S. monetary policy, according to an article at the South China Morning Post.

China’s skepticism has been reinforced by growing uncertainty around U.S. monetary policy, according to an article at the South China Morning Post.

The supposed independence of the Federal Reserve has been openly questioned during Trump’s presidency with tensions escalating with Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s revelation that the administration launched a criminal investigation into him.

Powell believes the probe stems from his refusal to set interest rates in line with the president’s preferences; Trump denies any knowledge of the investigation. Whatever the case may be, Powell’s chairmanship expires in May.

Shao expects that uncertainty to shape Beijing’s decisions going forward. “[Trump’s] appointee will undoubtedly be more compliant,” he says.

“This implies that, in line with Trump’s directives, there may be a push for rapid interest rate cuts and the initiation of large-scale quantitative easing to support infrastructure, including the artificial intelligence bubble.”

Rather than exiting global markets altogether, China appears to be rebalancing its reserves. Beijing is shifting assets toward gold, non-U.S. currencies and overseas equity investments.

Rather than exiting global markets altogether, China appears to be rebalancing its reserves. Beijing is shifting assets toward gold, non-U.S. currencies and overseas equity investments.

China added 30,000 ounces of gold in December, extending its buying streak to 14 consecutive months and bringing total reserves to 74.15 million ounces, according to official figures.

It’s also worth mentioning that China’s pullback stands in sharp contrast to the behavior of other major investors.

Total foreign holdings of U.S. Treasuries rose to a record $9.36 trillion in November, up from $9.24 trillion in October. Japan and the United Kingdom — the two largest foreign holders — both increased their positions, as did Belgium and Canada.

While global investors still see U.S. debt as indispensable, Beijing is no longer willing to anchor its reserves to a system it increasingly views as politically unstable and fiscally unsustainable.

![]() Friday Follow-up: Silver

Friday Follow-up: Silver

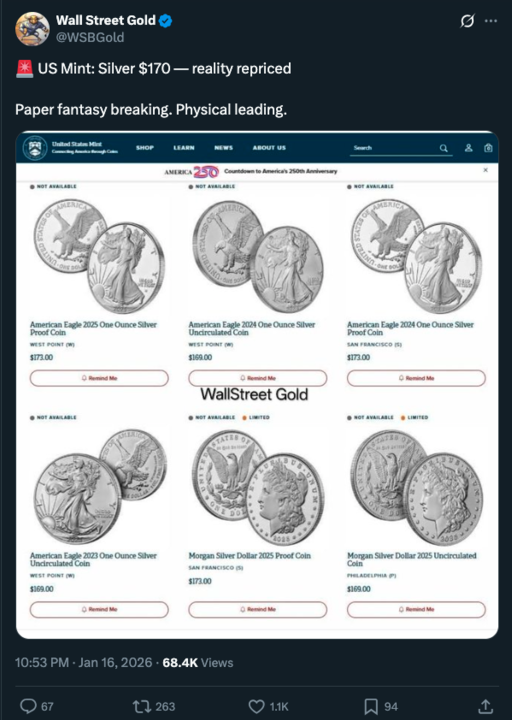

When silver moves faster than the U.S. Mint’s pricing software, you’re no longer in a normal market. This wasn’t just a website glitch. It was a market shock catching the government flat-footed.

When silver moves faster than the U.S. Mint’s pricing software, you’re no longer in a normal market. This wasn’t just a website glitch. It was a market shock catching the government flat-footed.

When the Mint did come back online at sharply higher premiums…

… that’s your confirmation that physical demand has pulled retail pricing out of sync.

![]() O’Hare Tests Limits of Naming Rights

O’Hare Tests Limits of Naming Rights

Chicago officials are floating the idea of selling naming rights across O’Hare airport — not just to terminals or concourses. Restrooms. Pet relief areas. Elevators. EV chargers. Trash cans. If it exists within the airport ecosystem, it’s apparently brandable.

Chicago officials are floating the idea of selling naming rights across O’Hare airport — not just to terminals or concourses. Restrooms. Pet relief areas. Elevators. EV chargers. Trash cans. If it exists within the airport ecosystem, it’s apparently brandable.

And O’Hare needs new satellite concourses and a rebuilt global terminal, but public infrastructure costs real money. If a company — or individual — wants to slap its name on a water fountain to help pay for it, why not?

This is Chicago, after all. The same city where the Chicago Bears are flirting with a stadium relocation — to Indiana — for tax reasons.

When your 100-plus year old football team is considering crossing state lines to dodge levies, it’s not shocking that your airport is wondering whether Gate B12 could pick up a corporate sponsor.

Of course, there are still many questions about how this all plays out in practice. And while it may raise revenue, it also sends a message. And not necessarily one the city intends.

Still, if Chicago is going down this road, it might as well lean in. Just don’t be surprised if the loudest applause ends up going to whoever sponsors the trash cans — the only thing at O’Hare that predictably handles volume.

Speaking from personal experience, O’Hare already owns the record for the longest layover of my life.

You all take care! We’ll be back tomorrow…